I find wearables to be very dynamic pieces of technology, as their use is often extended beyond their traditional function in a multitude of ways. The best example is a smartwatch; the dominant purpose of one is to tell time, but since it's already on your wrist, it's perfectly poised to also gather information on your pulse and track your movement through the day.

Since masks have become a staple this year, I thought that there might be untapped potential to implement peripheral technologies, particularly when it comes to health data. The mask is already positioned well to gather data about your breath, and how the composition of your breath can give better insights about your health.

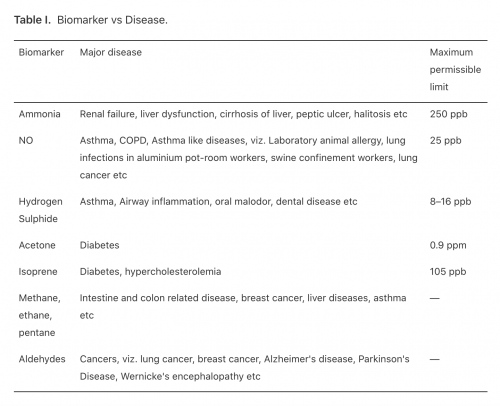

Specifically, you can monitor breath composition by analyzing the bVOCs, or breath Volatile Organic Compounds. The most important biomarkers of diseases in human body are ammonia, acetone, isoprene, nitic oxide, hydrogen sulphide, methane, ethane and pentane.

The Build

The build was a little tricky to get perfect due to two factors: One, the microcontroller needed to be quite small and contained to fit within the mask, but at the same time have IoT capabilities; and two, the gas sensor(s) needed to have a wide range of bVOCs, while also being small enough to fit in the mask.

This meant that I ruled out using the LilyPad ecosystem due to the fact that it was difficult to make it into an IoT device. This also meant that I couldn't use the MQ sensors because of their size, even though they provide individual readings for each biomarker.

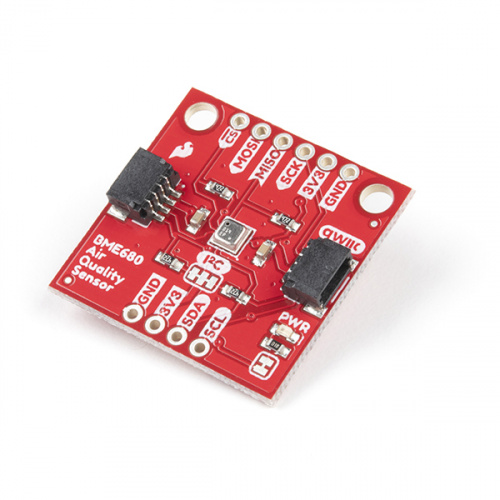

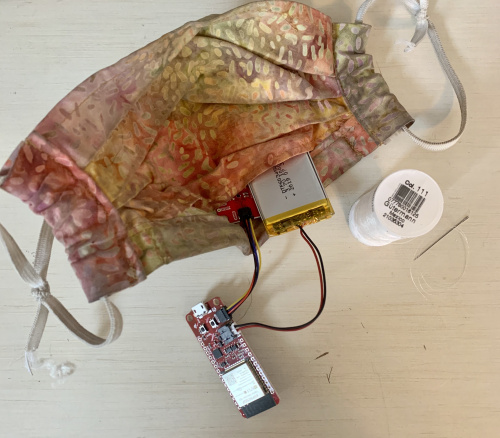

Instead, I settled on using the BME680 Environmental Sensor Breakout, which can easily connect to the ESP32 Thing Plus via Qwiic, and get power through a single-cell LiPo battery. While it still isn't the most ideal build, it was the best compromise between size, IoT capabilities, and range of bVOCs.

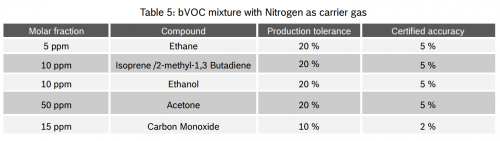

The BME680 produces a breath VOC equivalent output (bVOCeq) based on a bVOC mixture that represents the most important compounds in an exhaled breath of healthy humans, as seen in the table below. However, this means that it isn't able to distinguish any specific bVOC compound from the read out value - only whether the overall gas concentration has increased or decreased.

The Code

As a raw signal, the BME680 will output resistance values and its changes due to varying VOC concentrations. Since this raw signal is influenced by parameters other than VOC concentration (like humidity level), the raw values are transformed to an IAQ (Indoor Air Quality) index by BSEC smart algorithms. Therefore, to get true IAQ values to determine the bVOCeq we have to use Bosch's BSEC Arduino Library, which uses an algorithm to convert the resistance value to an IAQ value.

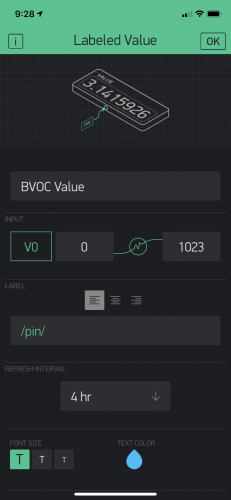

Since the mask needs to be an IoT device, we'll create a Blynk app, so we'll need to manipulate the code to include a Blynk authentication token, WiFi credentials, and serial to run the app.

The Results

Even with the smart algorithm from Bosch, the values are still a bit varied. The current values are high (bVOCe ppm is upwards of 900), but it's also important to remember that higher VOC concentrations are typically indicated by lower raw gas values. I think I'll give the sensor time to calibrate itself and see if the values change, otherwise I'll have to go back and reinterpret the results!

Here is my little homemade mask, built up and ready for use! The weight of the build doesn't actually make too much of a difference when I'm wearing the mask, which is a plus. As for next steps, I really think that masks will be an effective wearable for future since they're so prevalent in our everyday life right now. In this project I focused on health, but some other interesting applications could be language translation through ML, or customizable LED apps that complement the mask.

No comments:

Post a Comment